The latest reservation policy, which was adopted one and a half decade ago in the wake of the 2006 Multiparty Democracy Movement, has been at the center of the ongoing discourse about reservation in Nepal. But reservation is not a new practice. Some form of reservation has always existed in Nepal since its foundation. This article is a brief examination of various reservation policies adopted by Nepal in its history.

If reservation is to be defined as a practice to guarantee public posts, means or resources to certain castes, communities or gender groups, Prithvi Narayan Shah should be viewed as the first propagator of the idea of reservation. Through his Divya Upadesh, Shah has reserved several public posts for certain clans, castes and members of his extended family. For example, the post of Karpadari was exclusively meant for the members of Kalu Pandey's family. Diplomatic postings in India and Tibet were meant for the families of Kalu Pandey and Shiva Ram Basnyat. The posts of Kaji were reserved for Pandey, Basnyat, Panta and Magar. This meant those posts were not available for people belonging to other families or clans. It is a clear case of reservation.

Muluki Ain reserved high-ranking posts for the so-called Hindu hill upper caste people.

But those clans and families who benefitted from Prithvi Narayan Shah's policy do not want to call it for what it is: reservation. They want to hide or underplay the historical fact that they enjoyed monopoly over lucrative public posts, facilities and power because of what can be described as an informal form of reservation. It is akin to a tyrant not describing his administration as tyranny. But a tyrant is a tyrant no matter how he describes himself. A reservation policy is a reservation policy even if it is not called so by those who would benefit from it.

Junga Bahadur Rana perpetuated the Prithvi Narayan Shah-era style of reservation by enacting Muluki Ain, the civil code of the country. Muluki Ain reserved high-ranking posts for the so-called Hindu hill upper caste people. As in the Shah era, it was an anti-inclusion form of reservation. Even the monarchy and the Rana oligarchy benefitted from a form of reservation, which did not allow people from other families to become king or Prime Minister.

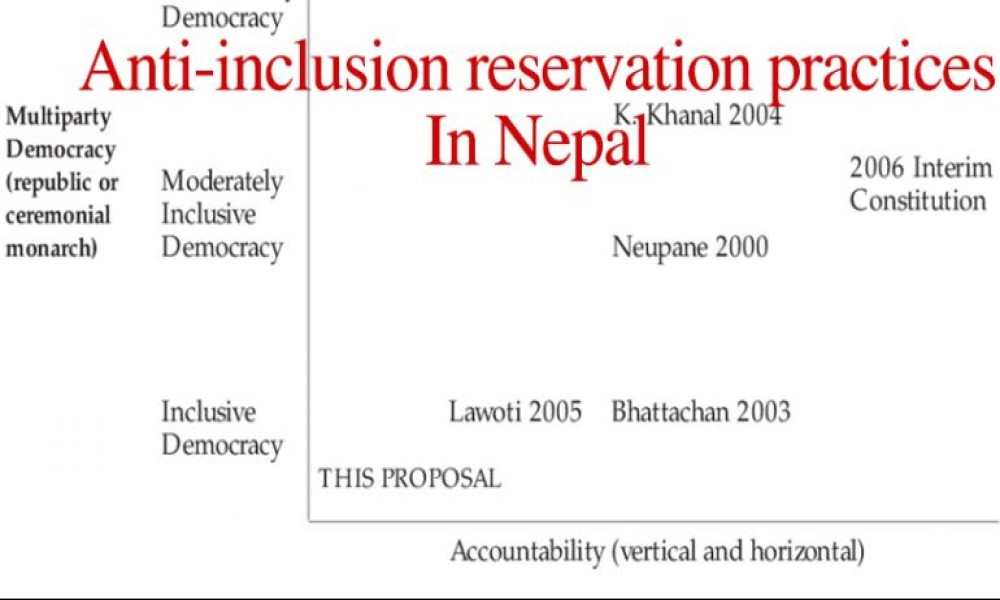

The continuous dominance of the Khas-Arya caste groups in Nepal's government, parliament, judiciary, bureaucracy, military and police force is a result of anti-inclusion reservation practices.

The practice of informal reservation did not end even after the criminalization of caste-based discrimination and untouchability. The continuous dominance of the Khas-Arya caste groups in Nepal's government, parliament, judiciary, bureaucracy, military and police force is a result of anti-inclusion reservation practices.

Such an informal form of anti-inclusion reservation is perpetuated by promoting the dominant caste groups' cultures and values as superior to those held by other communities. For example, in a multi-lingual country like Nepal, only Nepali language was promoted by the State. The exams of Public Service Commission (PSC) were conducted in Nepali language, making it difficult for people from other linguistic groups to crack the exams. This form of reservation needs to be replaced by a reservation policy that nurtures inclusion and increases the access of all castes, ethnic groups, genders and communities to the State.

(This is an official and summarized translation of Prof. Lawati's article originally written in Nepali language and published in Kantipur daily-editor)