- By Manika Budhathoki Magar

Growing up as an indigenous girl in a diverse city neighbourhood, my heritage felt distant. It was only during village visits for festivals that I truly connected with my culture. I'd borrow my cousins' Magar outfits, the vibrant yellow patuka—a long piece of cloth tightly wrapped around the waist—feeling both discomfort and a strange sense of belonging. When I requested my mother loosen the patuka, hindering my breath, her refusal was firm. A loose patuka, she explained, would expose my lower half, a social faux pas. This early experience reflected the constant negotiation indigenous women face: compromising comfort and identity for societal expectations.

This struggle for identity extends far beyond childhood. Indigenous women navigate a double bind of patriarchy, both within their communities and from the dominant Nepali society. Caught between societal pressures, they fight for basic rights while battling stereotypes and misconceptions.

The Intersection of Feminism and Indigenous Identity

Nepal's constitution enshrines equality, but the deeply entrenched caste system undermines its spirit. True inclusivity requires listening to the voices of indigenous women, who make up nearly half the country's female population. A misconception exists that indigenous women enjoy greater freedom due to some matrilineal practices. However, this narrative deserves a nuanced discussion within these communities themselves.

As of 2020, women hold over a third of elected positions across all branches. Yet, how many indigenous women are truly visible in decision-making roles? The numbers remain dismally low.

The 1970s saw the rise of Nepali feminism, advocating for women's participation in development. However, the late 1990s marked a shift towards acknowledging the specific needs of indigenous and marginalised women. Inspired by the third wave of Western feminism, which emphasized intersectionality, the Nepali movement recognized the limitations of a one-size-fits-all approach. Indigenous women found solidarity with Madhesi, Dalit, and Muslim women who shared experiences of exclusion. Their struggles were often overshadowed by the mainstream women's rights movement, which faced far greater discrimination due to their caste and ethnicity.

Legislative progress has ensured quotas for women and underrepresented groups in government. As of 2020, women hold over a third of elected positions across all branches. Yet, how many indigenous women are truly visible in decision-making roles? The numbers remain dismally low.

Stereotypes and Objectification

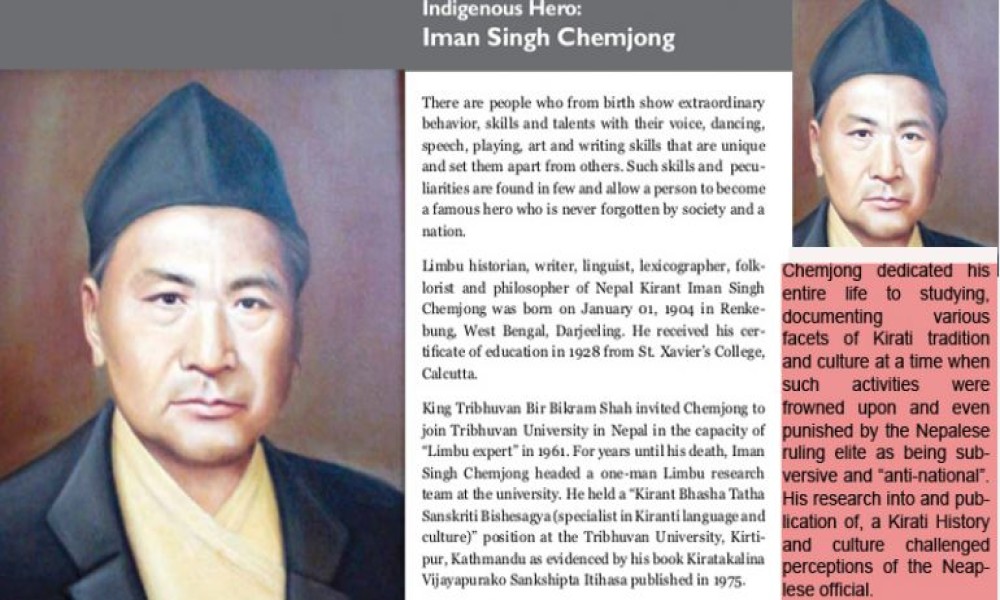

The limited representation of indigenous women in policymaking, academia, and advocacy spaces is a constant source of frustration. During a recent discussion on indigenous girls' issues, a student from the Tamang community shared her experience of a teacher who, assuming her limited prospects, encouraged her to pursue education to avoid early marriage – a stereotype many indigenous women encounter.

Media portrayals often perpetuate objectification. Newspaper articles on cultural festivals feature photos of indigenous women solely in traditional attire, dancing or parading. This reinforces the notion that these women are readily available for sexual gratification and possess limited professional skills. Such portrayals contribute to the vulnerability of indigenous women to trafficking, as highlighted by the National Human Rights Commission's report stating that 49% of trafficking survivors are indigenous.

Discrimination and "Othering"

Despite their rich cultural heritage and knowledge, indigenous women face a harsh reality of discrimination and exclusion. Their very Nepali identity is questioned, with remarks about their appearance not conforming to a narrow definition. These experiences highlight the persistent racism that indigenous women confront, existing alongside the patriarchy within their own communities.

Despite their rich cultural heritage and knowledge, indigenous women face a harsh reality of discrimination and exclusion.

An illustrative example: a social media post celebrating indigenous girls elicited a response questioning whether the Khas nationality belonged to the "indigenous group," claiming Khas men, particularly Brahmins, were the most suppressed people in Nepal. Explaining the complexities of marginalisation to someone who is unwilling to understand is an exhausting exercise. Indigenous women are doubly targeted: by the dominant Nepali society and by patriarchal structures within their own communities.

Underrepresentation and Missed Opportunities

A long history of marginalisation, poverty, and exclusion has limited the opportunities for indigenous women to participate in decision-making processes. They are often stereotyped as less intelligent and politically astute compared to others. Research confirms their underrepresentation in positions of power. This intersection of gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background creates a web of vulnerability, impacting their access to education, professional opportunities, and increasing the risk of gender-based violence.

The majority of indigenous communities reside in rural areas, with limited access to education and resources. Despite managing over 80% of Nepal's biodiversity resources, as per UN Women 2016, their deep understanding of medicinal plants and traditional knowledge goes unrecognised.

The contemporary lives of indigenous women haven't strayed far from the past. Their voices remain unheard, and their needs remain unaddressed. Their invaluable knowledge, roles, and perspectives are missing from crucial decision-making processes on political representation, economic self-sufficiency, and international relations. Despite their rich cultural heritage, indigenous women hesitate to step forward, leaving their stories untold. The question remains: How many more voices are waiting to be heard?