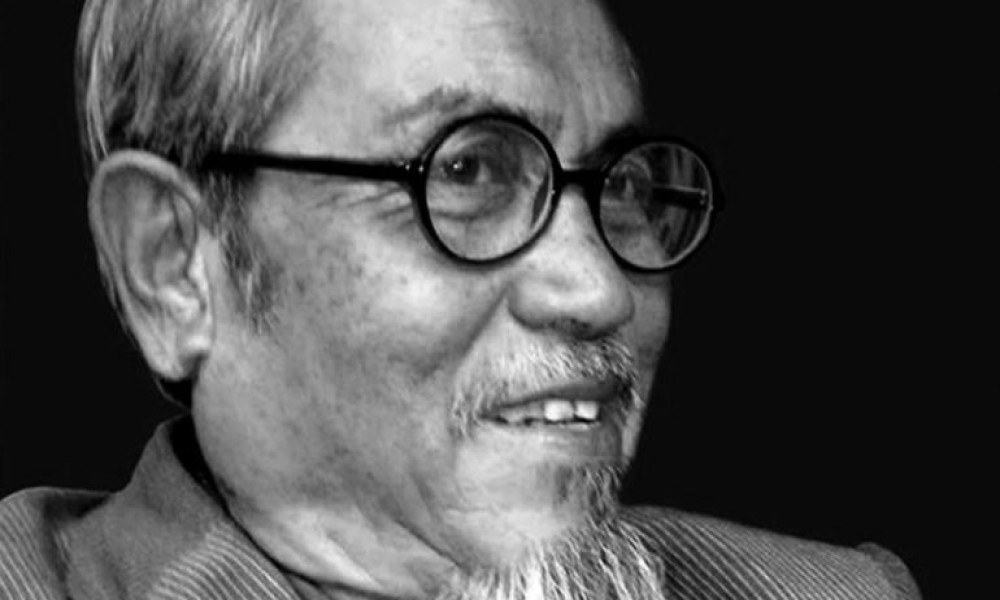

After being severely injured in a road accident three years ago, Gore Bahadur Khapangi was never able to get up, and stand on his own feet. He was hospitalised and then bedridden in his own house for a long time. He passed away last week.

After Khapangi's departure, some political analysts remembered him as a communist. True, he was a communist in the early years of his political career. He studied, debated and followed Marxism and Leninism. But it would not be fair to remember him just as a communist.

Khapangi formed his own political party that catered to the Adivasi Janajati constituency. Why did he have to deviate from the mainstream communist politics, and championed the cause of the oppressed and marginalised Indigenous People. Without analysing why he had to form a party of his own, it would not be possible to imagine an equal society he fought for.

Khapangi also led a campaign to boycott Dashain, arguing that it is a celebration of the victory of Bahuns and Chhetris over Adivasi Janajatis.

A school teacher in Ramechhap district, Khapangi quit his job to join the then-underground Marxist-Leninist party. But he felt suffocated in the communist party, and initiated a long struggle for the liberation of Nepal's oppressed indigenous communities. He often said: "To be under a political party led by a Bahun or Chhetri is to accept to be their slaves!"

Khapangi fought for proportional representation of indigenous people in state organs, federalism and secularism. Khapangi's Rashtriya Janmukti Party did not defeat mainstream parties in elections, but it emerged as a force to reckon with. It laid the foundation of identity politics on which the Maoists cashed in during the war.

Khapangi was an eloquent speaker. A thinker too. But he was a poor organiser.

Khapangi also led a campaign to boycott Dashain, arguing that it is a celebration of the victory of Bahuns and Chhetris over Adivasi Janajatis. But he accepted Tika from the king during a Dashain, prompting others to dub him a hypocrite. But he took all criticism in his strike, and continued to fight for recognition of the identity of indigenous people. He was dubbed an anti-Bahun. But all he did was oppose Brahminism, which is not exclusively associated with a particular caste or community.

Lack of political awareness among indigenous people perturbed Khapangi. He was disappointed that Janajatis were not aware about political structure that marginalised them. He praised the first Madhes uprising that brought the Big Parties to their knees, and forced them to include the word 'federalism' in the Constitution.

Khapangi was an eloquent speaker. A thinker too. But he was a poor organiser. He could not strengthen his party, failed to stop it from splitting. However, Khapangi's legacy as a champion of ethnic identity will always remain.