A reality check :

The promulgation of Nepal's new constitution has deeply polarized the Nepali society. Some are saying it is not progressive and inclusive, but others are saying it is even more inclusive than India's. This article is an attempt to draw a parallel between the Nepali and Indian constitutions in terms of inclusion.

Nepal's constitution is certainly progressive than India's in terms of granting rights to women, but it has failed to adhere to the principles of inclusion when it comes to Adivasi Janajatis, Madhesis and other marginalized communities.

India's constitution has recognized as many as 22 languages as official languages of the country. These official languages can be used in government offices and schools. But how many languages in Nepal have been recognized as official by our new constitution? The same old Khas-Nepali language. Other languages have been treated as second-class languages.

Nepal's constitution is certainly progressive than India's in terms of granting rights to women, but it has failed to adhere to the principles of inclusion when it comes to Adivasi Janajatis, Madhesis and other marginalized communities.

India's constitution has reserved government seats for Dalits and Janajatis in proportion to their populations. Dalits are entitled to 15 per cent of the total seats in parliament, bureaucracy and higher education. Janajatis are entitled to nine per cent of the total seats. Since 1992, people belonging to Other Backward Caste (OBC) get 27 per cent of the total seats in public service and higher education.

Nepal's constitution has envisioned that 60 per cent of parliament members will be elected directly. Only 40 per cent will be chosen under the Proportional Representation (PR) system. But these 40 per cent PR seats are not exclusively meant for marginalized communities. Bahuns and Chhetris will also be elected under the PR system. Minus them, only 27 per cent of the PR seats go to Dalits, Adivasi Janajatis, Madhesis, Muslims, Tharus and backward regions. The constitution has reserved 33 per cent seats for women. So, to meet this constitutional criteria, a chunk of the PR seats will be given to women. If the past is anything to go by, most Bahun and Chhetri women will get these PR seats.

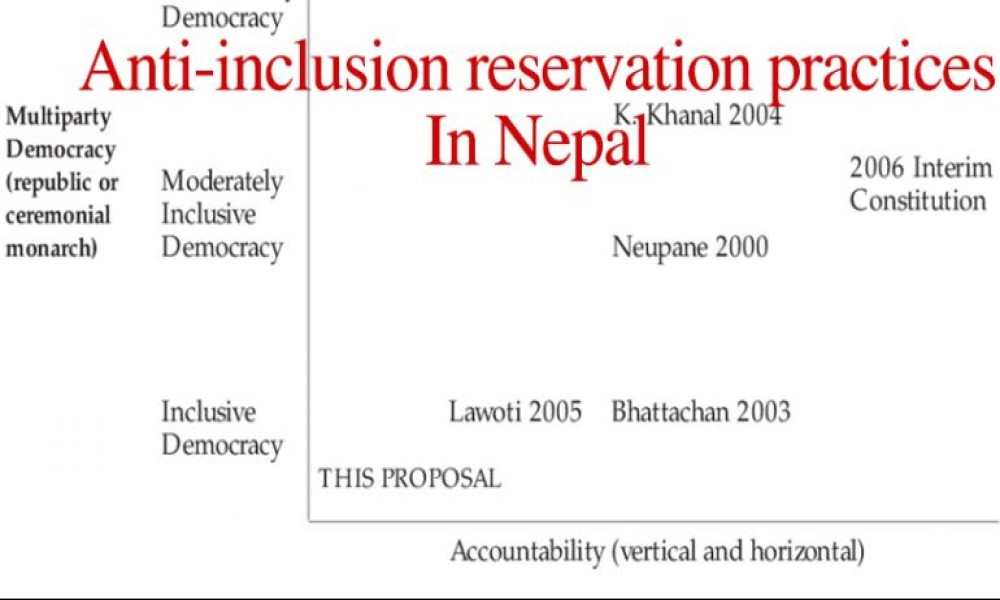

India's constitution has reserved seats only for marginalized communities. But Nepal's constitution has diluted the very concept of reservation by allocating PR seats even for the privileged communities like Bahuns and Chhetris.

In the present political system, very few women manage to win elections. In 2012, only 4.16 per cent of the elected parliament members were women. This percentage was slightly higher (12.03) in 2008. But it was even lower in 1999 (5.85 per cent), 1994 (3.90) and 1991 (2.92). So, to ensure that women get 33 per cent seats, they must be given a significant share of the PR quotas. And major political parties have so far never considered choosing more women from Dalit, Janajati, Madhesi and other marginalized communities.

After allocating a significant portion of the PR seats for Bahun and Chhetri women, very few remain for other backward communities. For example, let us calculate how many seats Dalits will get out of the PR quotas. The average percentage of elected women parliament members is 5.77 per cent. If this trend continues into the next election, 77 of the total 110 PR seats of parliament need to be allocated for women to ensure their 33 per cent reservation. Only 33 seats remain for marginalized communities, and Dalits will end up getting just two or three seats. Other marginalized communities will also get fewer seats than their proportions of Nepal's population.

India's constitution has reserved seats only for marginalized communities. But Nepal's constitution has diluted the very concept of reservation by allocating PR seats even for the privileged communities like Bahuns and Chhetris.