Navin Loharung Rai

Prithvi Narayan Shah, the king of the Gorkha principality who conquered weaker kingdoms and gave birth to what is now known as Nepal, preached us that our country is 'a garden of four castes and 36 sub-castes.' His descendant Mahendra Shah preached us about 'one language, one attire, one religion, one culture and one nation'. Now when Adivasi Janajatis, Madhesis and other marginalized communities are talking about state-restructuring, federalism and inclusion, we are once again being preached about nationalism and national unity.

Unfortunately, nation building has always been intertwined with internal colonialism and imperial mindset in Nepal. In the name of nation building, laws and policies were introduced by the state to deepen marginalization of ethnic communities. So when the ruling class talks of nationalism and national unity, we sense that they are up to something sinister yet again. We have learnt from our experience that centralization of power always masquerades as nation-building.

Nation building has always been intertwined with internal colonialism and imperial mindset in Nepal. In the name of nation building, laws and policies were introduced by the state to deepen marginalization of ethnic communities.

Exclusion emerged as a topic of debate in the 1970s, when people in France rose up against political and economic exclusion. Rene Lenoir was one of the first ones to begin a discourse on exclusion of physically disabled, elderly, children, drug addicts and single women in 1974. By the end of 1980s, several European countries acknowledged exclusion as a problem and came up with programs to tackle it.

Near home, India began inclusive policies in health, education, drinking and social safety in the early 1990s. Venezuela, Cameron and Thailand also introduced policies to mainstream the excluded communities. Policies of inclusion vary from country to country, but they all have imbibed in them principles of equality.

In Nepal, the state imposed discriminatory policies and perpetrated exclusion of a majority of the population for more than two centuries.

Whether in language, religion and culture, discriminatory policies were found everywhere. As a result, the marginalized communities suffered from economic, political, religious and economic problems.

In Nepal, the state imposed discriminatory policies and perpetrated exclusion of a majority of the population for more than two centuries. Whether in language, religion and culture, discriminatory policies were found everywhere. As a result, the marginalized communities suffered from economic, political, religious and economic problems.

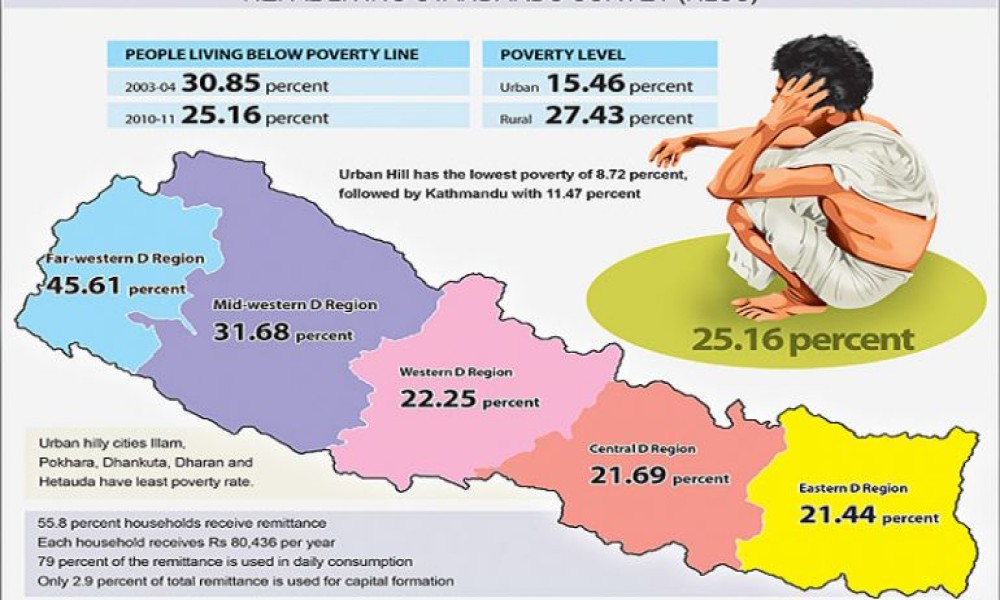

According to the Human Development Index 2009, Dalits are the poorest community, with 45.5 per cent of them struggling to make ends meet. Janajatis, whether in the hills or the Tarai, also do not fare well. In the hills, 44 per cent of Janajati people are poor while this is around 35 per cent among Janajatis in the Tarai. Poverty percentage is 41 in the Muslim community. But only 18 per cent of people are poor in the Bahun-Chhetri community.

The percentage of poverty was not as low as now in the Chhetri-Bahun community. But with favorable policies by the state, they were able to come out of the cycle of poverty but other marginalized communities continue to remain poor even now. So exclusion and poverty are interlinked. If we are to develop our country, we must ensure equality. And for this to happen, the ruling class must stop fearing federalism and be receptive to inclusion.