Those who were in power imposed their language and script over those who were not in power. The felt excluded and held protest rallies on the streets. Their protests were ‘unlawful’ in the eyes of the ruling class, who tried to silence the dissenters. Tear gas shells were hurled, and batons were charged at the protesters. But the demonstrators did not retreat, and security forces opened fire killing three students.

This incident took place in the morning of February 21, 1952 in front the parliament building in East Bengal, sparking widespread protests over the Urdu-speaking ruling community’ policy of imposing their language over the Bengali-speaking community. The protests triggered by the discriminatory linguistic police flared up, eventually leading to Bangladesh’s secession from Pakistan.

The State’s one-language policy and the linguistically excluded communities’ rebellion against it have split many countries – not just Pakistan – around the world. Many countries in Europe, Latin America and Africa have been created against the backdrop of conflicts triggered or fueled by the State’s discriminatory linguistic policies. In linguistically diverse countries such as Nepal, there is a much higher probability of conflict, war and even secession, which can be avoided if the State adopts right linguistic policies and approaches.

Fearing potential conflict between different language groups, and hoping to maintain social cohesion, Nepal’s intelligentsia, civil society leaders and democratic forces have long stressed the need for linguistic justice and equality. The Nepali state has also adopted a principle that all mother tongues spoken in the country are national languages, and that they are equal.

The State has recognized that Nepal is linguistically, socially, culturally and religiously diverse country, and unity in diversity is a tenet of Nepal’s nationalism.

Nepal’s Interim Constitution 2007 was a milestone in ensuring linguistic justice. Nepal’s Constitution 2015 has also recognized Nepal’s linguistic diversity, and the constitutional status of diverse languages. The State has recognized that Nepal is linguistically, socially, culturally and religiously diverse country, and unity in diversity is a tenet of Nepal’s nationalism.

What is important to recall here is that Nepal’s national character developed during the 250 years of absolute monarchy was defined by the State’s ‘one language one attire, one king one country’ principle. The hill Brahmin chauvinism was the DNA of that national character. In the eyes of the ruling class, languages other than Khas-Nepali were uncivilized and barbaric. The ruling class believed that these diverse languages were a hurdle in the process of national building, and that they can be eradicated by adopting the one-language policy.

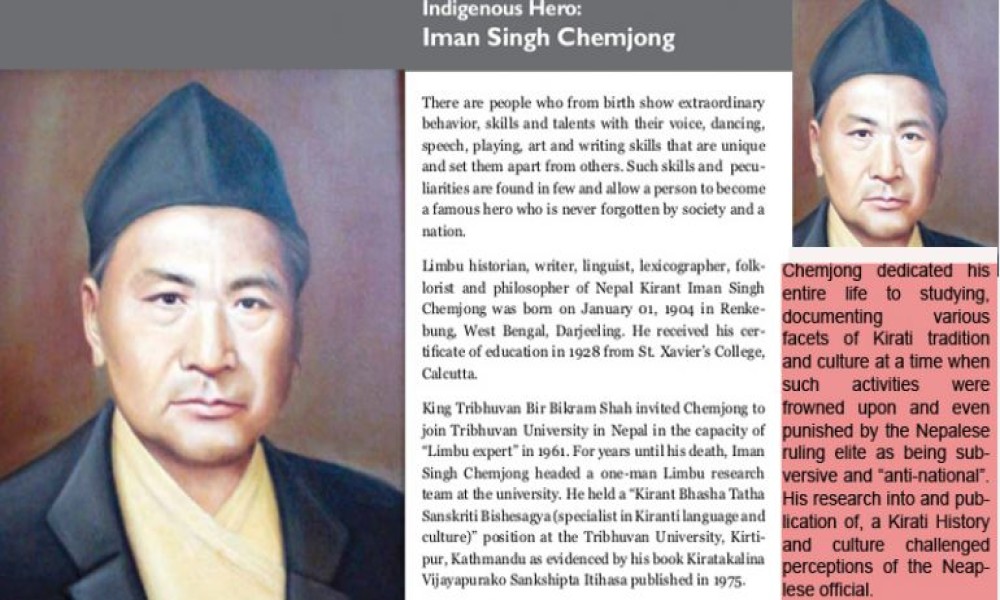

Various historic documents show how Nepal’s rulers tried to cement Khas-Nepali’s status as the official language at the expense of marginalizing a myriad of mother tongues. The Shah rulers’ policy of restricting other languages forced many indigenous Limbu people to flee to Sikkim. Those Limbus who wanted to use their own Sirijunga script instead of Devanagiri were jailed in eastern Nepal. In Kathmandu Valley, many were punished for preaching Buddhist wisdom in their own Newari language. Siddhicharan, Chittadhar and Phatte Bahadur were sentenced to life imprisonment. Their property was also seized by the State. The ruling Khas-Nepali community’s linguistic chauvinism reached peak towards the end of the party-less Panchayat era.

Children were restricted from learning in their mother languages. They were forced to learn Khas-Nepali language in school. In the media, the court and official works, only Khas-Nepali language could be used.

Children were restricted from learning in their mother languages. They were forced to learn Khas-Nepali language in school. In the media, the court and official works, only Khas-Nepali language could be used.

Here is a testament to the height of linguistic chauvinism demonstrated by the ruling class. In the early 80’s, Padma Ratna Tuladhar was in the Nakkhu jail for criticizing the royal palace during a protest rally. His mother went there to see his son, and they started talking in the language they would speak at home: Newari. But she was not allowed to speak in her mother tongue. She was forced to speak in Nepali – the language in which she was unable to express her feelings and emotions.

The State’s such discriminatory one-language policy, linguistic chauvinism and oppressive actions were the reasons behind the fall of the Shah dynasty. Nevertheless, the new ruling class’s thinking and actions regarding language policy are not much different. The latest example of it is the arrest of some Newar protesters for speaking in their own language. It all started with a clash between local Newar youth and police in Balaju, Kathmandu. Local people of Balaju are against the widening of a road, but the administration is determined to do it despite a Supreme Court order against it. On February 24, police arrested some local protesters for ‘obstructing the road widening drive’. Those who met them in policy custody were also arrested. Their ‘crime’ was that they spoke in their mother tongue at a police station.

Language is not just a means of communication; it is also people’s identity. The time has changed, the country has changed, Nepalis are no longer subjects to the rulers.

What else can be a more telling example of the State’s exclusionary linguistic chauvinism? Khas-Nepali was already made mandatory in schools, government offices and court rooms. Now people have been barred from even talking to their friends and family members in their mother tongues at a police station. Is police’s act of barring people from speaking in their mother tongue constitutional? Is it as per the State’s policy? The reign of the State has clearly gone to the hands of wrong people, who did not digest the achievements of the 2006 pro-democracy movement. They are inclined to restoring Hindu supremacy and dismissing secularism. There are also slogans in favor of the deposed king.

The Balaju incident has raised several questions: is the ghost of the Khas-Arya chauvinism, which was cremated by people in 2006, making a return? Is it a sign of regression?

If the ruling class wants to impose their Khas-Nepali language over other communities, they would do well to recall what happened in Bangladesh. Language is not just a means of communication; it is also people’s identity. The time has changed, the country has changed, Nepalis are no longer subjects to the rulers. Nepalis are sovereign, and no one has the right in Nepal to say that people cannot speak in their mother tongues.

The unofficial translation of Malla K. Sundar’s article, which was published in Naya Patrika.