Nepal's indigenous rights movement has a long history, which begins with Gorkha emperor Prithvi Narayan Shah's military campaign 250 years ago. It ran through the Rana reign and the Panchayat regime, and continues even in today's republic. But most scholars focus only on its modern phase, particularly after the launch of the Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN) in the early '90s.

In this article, I will shed lights on the early stages of the struggle, analyzing its challenges and achievements so far before outlining the way forward.

Prior to the political change of 2046 BS, Nepal's indigenous rights movement was disorganized, and it was therefore somewhat muted. It was seen largely as a social movement detached from political goals and ambitions. But, even by then, it had witnessed many ups and downs in its long evolution.

Shah declared Nepal as a garden of all kinds of flower, reflecting the country's ethnic, religious and cultural diversity. But he endorsed the Hindu caste hierarchy, putting the hill Brahmin-Chhetri at the top of the social order.

In the second half of the 18th century, after annexing independent kingdoms of various ethnic communities into his Gorkha principality, Shah declared Nepal as a garden of all kinds of flower, reflecting the country's ethnic, religious and cultural diversity. But he endorsed the Hindu caste hierarchy, putting the hill Brahmin-Chhetri at the top of the social order. He also initiated the process Hinduization, imposing Hindu religion, culture and values over other religions, cultures and values.

Khas-Nepali language was decaled the national language. Even those ethnic communities who had their own mother tongues were forced to use Khas-Nepal as lingua franca. Cow, eaten by some ethnic communities, was declared the national animal. Those who ate beef were persecuted.

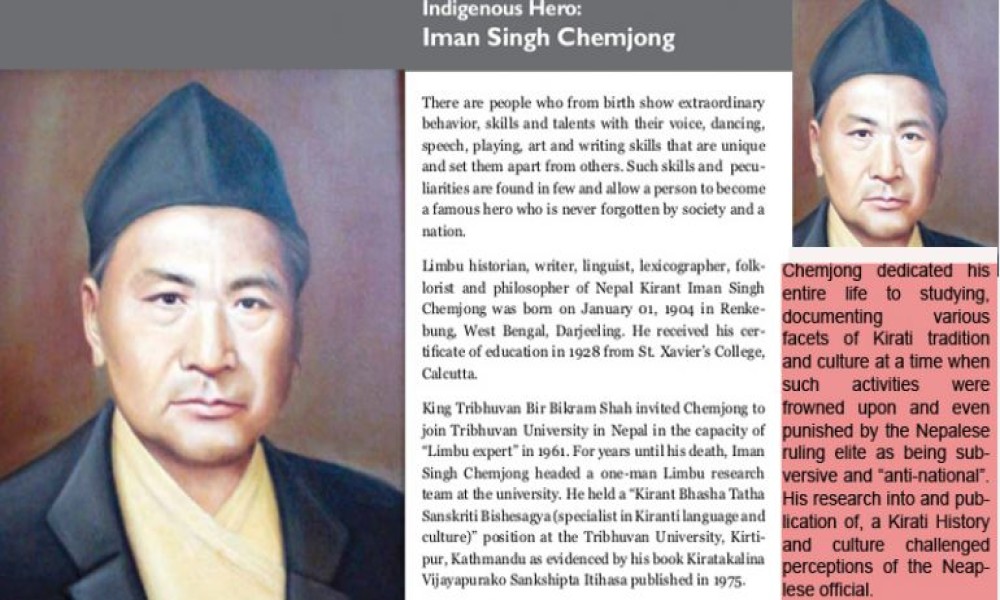

In 1835 BS, Limbus in the far-eastern hills had revolted against the imposition of Khas-Nepali language over their mother tongue. In 1850 BS, Tamangs of Nuwakot revolted against the state-sponsored cultural campaign for Hinduization, demanding cultural autonomy. In 1865 BS, Rais in the eastern hills fought against encroachment of their lands by outsiders. But the Shahs brutally crushed every revolution, massacring and chasing away rebels.

Khas-Nepali language was decaled the national language. Even those ethnic communities who had their own mother tongues were forced to use Khas-Nepal as lingua franca. Cow, eaten by some ethnic communities, was declared the national animal. Those who ate beef were persecuted.

The Ranas came to power after the infamous Kot Massacre in 1903 BS, and ruled the country for 104 years. Just like the Shahs, they used Hindu religion and culture as a weapon against Adivasi Janajatis. In 1911 BS, after his legendary trip to the UK, Junga Bahadur Rana, the founder of the Rana oligarchy, issued Muluki Ain, the law of the land. Hugely influenced by Manu Smriti of Hinduism, this law cemented marginalization of indigenous communities.

By banning the consumption of cow meat, this law deprived Sherpa, Bhote, Tamang and some ethnic communities of their cultural rights. Four years later, further outraged by the legalization of systematic marginalization, Sukdev Gurung in Lamjung led an uprising for autonomy. Nearly two decades later, in 1933 BS, Lakhan Thapa of Gorkha challenged the rule of the Rana clan. One year later, in the same Gorkha district, Supati Gurung rose against the Ranas. Meanwhile, Adivasi Janajati people in Dhankuta boycotted Dashain festival, dubbing it a Hindu festival.

The early acts of resistance were not organized, and did not really shake the Kathmandu establishment. Nevertheless, they helped raise awareness among Adivasi Janajati for their rights, and the need for autonomy and self-rule. The state became more tolerable to dissenting views after the fall of the Ranas in 2007 BS, and more so after the political change of 2046 BS.

In 2047 BS, associations of nine different ethnic communities (Gurung, Magar, Newar, Rai, Limbu, Tamang, Sherpa, Thakali and Sunuwar) founded the NEFIN. As one of the founding members of the NEFIN, Sunuwar society has always been active in indigenous rights movement. So, the NEFIN's achievements are also the achievements of Sunuwars.

The Maoists, during the war, gave voice to indigenous rights movement. In addition to supporting the issues of language, culture and identity, the Maoists pushed for federalism, ethnic identity based autonomous states, autonomy, rights to self determination and proportional representation of all marginalized communities.

The early acts of resistance were not organized, and did not really shake the Kathmandu establishment. Nevertheless, they helped raise awareness among Adivasi Janajati for their rights, and the need for autonomy and self-rule.

After the Democracy Movement of 2006, these issues became the crux of mainstream politics. Today, the Constitution has addressed some of these demands like federalism, but the indigenous rights movement is far from being over. Their aspirations for greater autonomy and identity remain unfulfilled. For example, the Constitution has not envisaged the kind of secularism that Adivasi Janajatis want. Proportional representation of Adivasi Janajatis, rights to self determination and ethnic identity remain unaddressed.

So, the struggle for indigenous rights still has a long way to go. In the past, the state has tricked the leaders of indigenous people into signing agreements that are dumped into the trash bin. Now, they must be aware of the conspiracy of the state, and stand united for their collective goals. There should be no room for compromise and back-tracking.